Telecoms executives already recognise that lack of collaboration poses the greatest threat to 6G. In TelcoForge’s Q4 Survey we explored what leaders from around the industry consider their biggest problems and the biggest challenges 6G implementation will face. Collaboration will be prioritised rhetorically in the early stages, but acted upon seriously only once competitive and financial pressures make coordination far harder to achieve.

The divergence between diagnosis and action

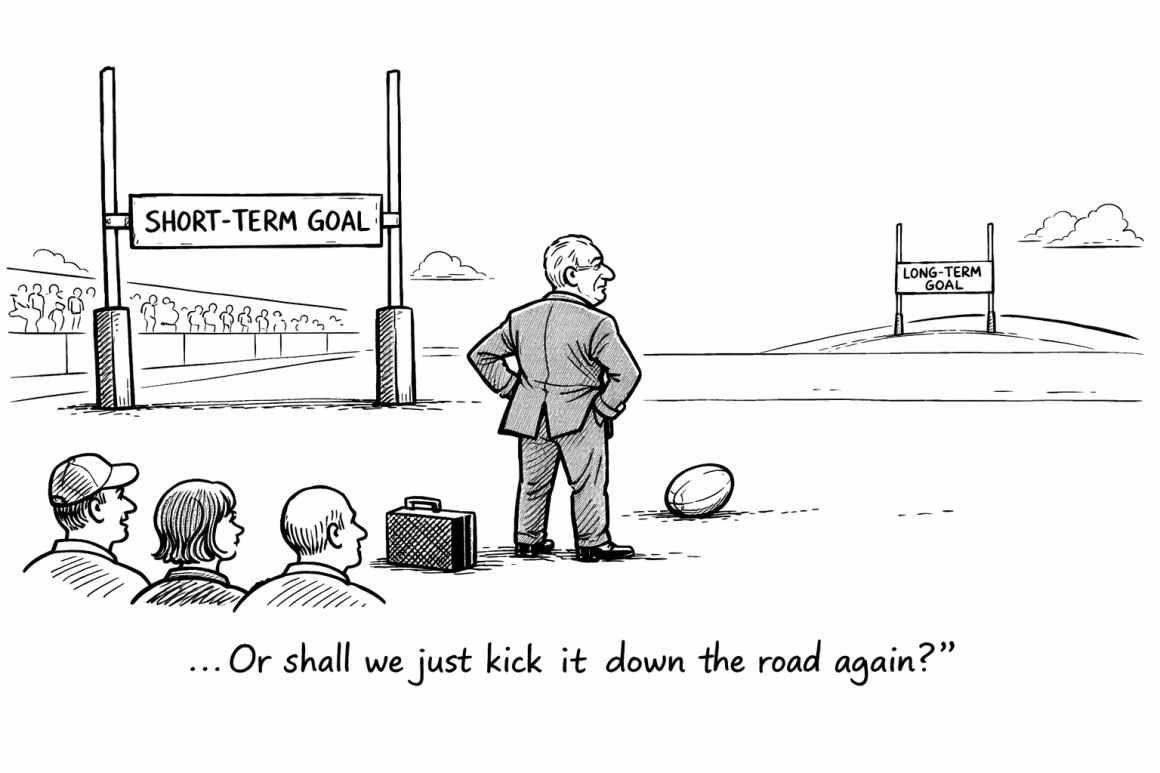

When asked about today’s operational challenges, executives cited skills shortages, AI-driven organisational change, and investment pressures. Yet when asked why 6G might fail, they overwhelmingly point to lack of industry collaboration. This apparent inconsistency reflects a pattern in executive decision-making which treats immediate and longer-term thinking differently.

Readers of Daniel Kahneman’s book “Thinking Fast and Slow” are familiar with the idea that people use different cognitive systems whether they’re looking at immediate or distant problems. Near-term issues trigger concrete, analytical thinking focused on constraints and execution. Long-term risks are processed more abstractly, shaped by narratives and past experience rather than operational detail.

Executives can simultaneously recognise collaboration as a future existential risk while devoting present-day attention to problems they experience directly and believe they can control. That sounds perfectly reasonable until the day you realise that time has passed and the perfectly predictable lack of collaboration or coordination has materialised.

Predicting priorities

Today, 6G exists mainly as a strategic consideration. Collaboration is framed as a shared industry good that ‘somebody should do something about – for example, something which standards bodies might handle. Because collaboration failures don’t impose costs on any specific executive yet, they don’t trigger detailed execution planning. The result of this is that there is strong alignment on intent, but a lack of specificity on incentives, governance, or trade-offs.

As 6G planning becomes more concrete towards the end of the decade, a shift is likely to occur. Collaboration remains valued, but increasingly viewed through different lens. Executives will begin favouring bilateral partnerships over multilateral ones (not least because they are easier to set up); they will want influence within standards processes rather than shared control; and prefer optionality over binding commitments. Organisational theorist James March described this as the tension between exploration (collective learning) and exploitation (competitive advantage). As stakes rise, the instinct towards exploitation becomes dominant.

Once real investment decisions arrive, collaboration is reframed as a potential source of delay, a threat to differentiation, and a constraint on commercial freedom. The psychological framing flips entirely. What was previously a collective necessity is now experienced as an execution cost. This aligns with research on loss aversion: the expected pain of near-term competitive loss outweighs the abstract benefit of long-term collective gain. Executives who previously warned that collaboration failures could doom 6G now find themselves rationally prioritising firm-level outcomes.

Three predictable gaps

This progression produces failure patterns that tend to repeat across industries:

First, collaboration is emphasised in vision statements and keynotes but weakly embedded in operating models and commercial structures. Industry cynics might point to efforts such as the Open RAN ecosystem, which has a lofty goal but some might say that the role played by major NEPs undermined the execution.

Second, serious coordination attempts occur only after fragmentation is visible, by which point architectures, vendor relationships, and incentives are already entrenched. Think about the scramble to make sense of 5G’s many versions after the politicking within the standards process.

Third, when collaboration falls short, blame shifts outward to competitors, vendors, regulators, or standards bodies, rather than reflecting on earlier internal trade-offs. As organisational theorist Karl Weick observed, people often retrospectively discover constraints that were in fact created by their own earlier choices.

6G is different

As noted above, this is not a new pattern for the industry. What makes it more dangerous for 6G is the context and intent.

6G is expected to span multiple industries; depend on shared platforms rather than standalone networks; and blur traditional boundaries between operators, vendors, and non-telco players, for example in delivering Joint Sensing & Communication services or coverage jointly across mobile and satellite players.

In such environments, late coordination is inefficient, yes, but it can also determine who captures the lion’s share of the value… and let’s be honest, since the end of walled gardens that hasn’t been the CSP’s strong suit.

Oh, behave!

The problem is behavioural rather than technical or informational, so the response must be too.

In the abstract, we might say that instead of treating collaboration as an aspiration, we should embed it in concrete mechanisms and agreements such as shared investment vehicles, pre-competitive platforms, binding interoperability commitments.

In practice, it means taking some of the voluntary forms of collaboration in the industry and giving them teeth. Within countries, government incentives for coordination and fora to make it happen may deliver more efficient, rational methods to deliver improved connectivity to end users; for example, to coordinate on a single secure infrastructure for future generations of fixed, mobile and satellite communications, or encouraging different methods of roaming to support service continuity.

Within industry bodies, it may involve changing decision-making criteria and transparency in order to reduce the effect of competitive jockeying. So, for example, we might separate out the companies voting on what technical solutions to adopt from those proposing them.

In other words, it’s about separating long-term coordination efforts from short-term performance metrics, much as safety functions are separated from quarterly targets in other industries. And just as engineers design systems to account for failure modes, industry leaders should design governance models that assume present bias, loss aversion, and competitive reflexes.

The hardest challenge

Telecom leaders understand what could derail 6G. The challenge is acting on that understanding before collaboration becomes seen as a cost.

If the industry waits until 6G is commercially imminent to take coordination seriously, it will be responding exactly as behavioural science predicts; repeating a pattern we know from experience is counterproductive; and leaves the door open for others to reap the benefits of operators’ investments.

Image courtesy of ChatGPT